My guest for this issue of Multiplier is Jane Fiona Kennington. Jane is the founder of the Perth-based Funny Fintan Softworks and game director of the upcoming Don’t Stop, Girlypop! She’s also a member of the WA Games Industry Council.

Fergus: If you’re in the market for the archetypal military shooter, the games industry still makes plenty of those and if the recent success of Call of Duty: Black Ops 6 is any indication, that formula can still be a winning one.

According to Microsoft, the biggest name in the game is still thriving. Despite the enduring popularity of its biggest tentpole franchise, the shooter genre has exploded into new and more experimental directions in recent years. Outside of the AAA space, there’s been a shift towards more stylised aesthetics. There’s a lot about this that makes sense. If you’re looking to play a shooter, chances are you’re not looking for one that reinvents the wheel entirely as much as you are one that offers you a different flavor than what you can play elsewhere.

If the recent boom in so-called “boomer shooters” are one side of this coin, then more off-the-wall efforts like Anger Foot, Bears in Space, 420BLAZEIT 2: GAME OF THE YEAR -=Dank Dreams and Goated Memes=- [#wow/11 Like and Subscribe] Poggerz Edition (yes, that’s the full title) or Incolatus: Don't Stop, Girlypop! are the other.

Style and substance often get framed in opposition to one another, but maybe that relationship is a little more complicated than we’d like to admit.

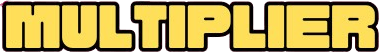

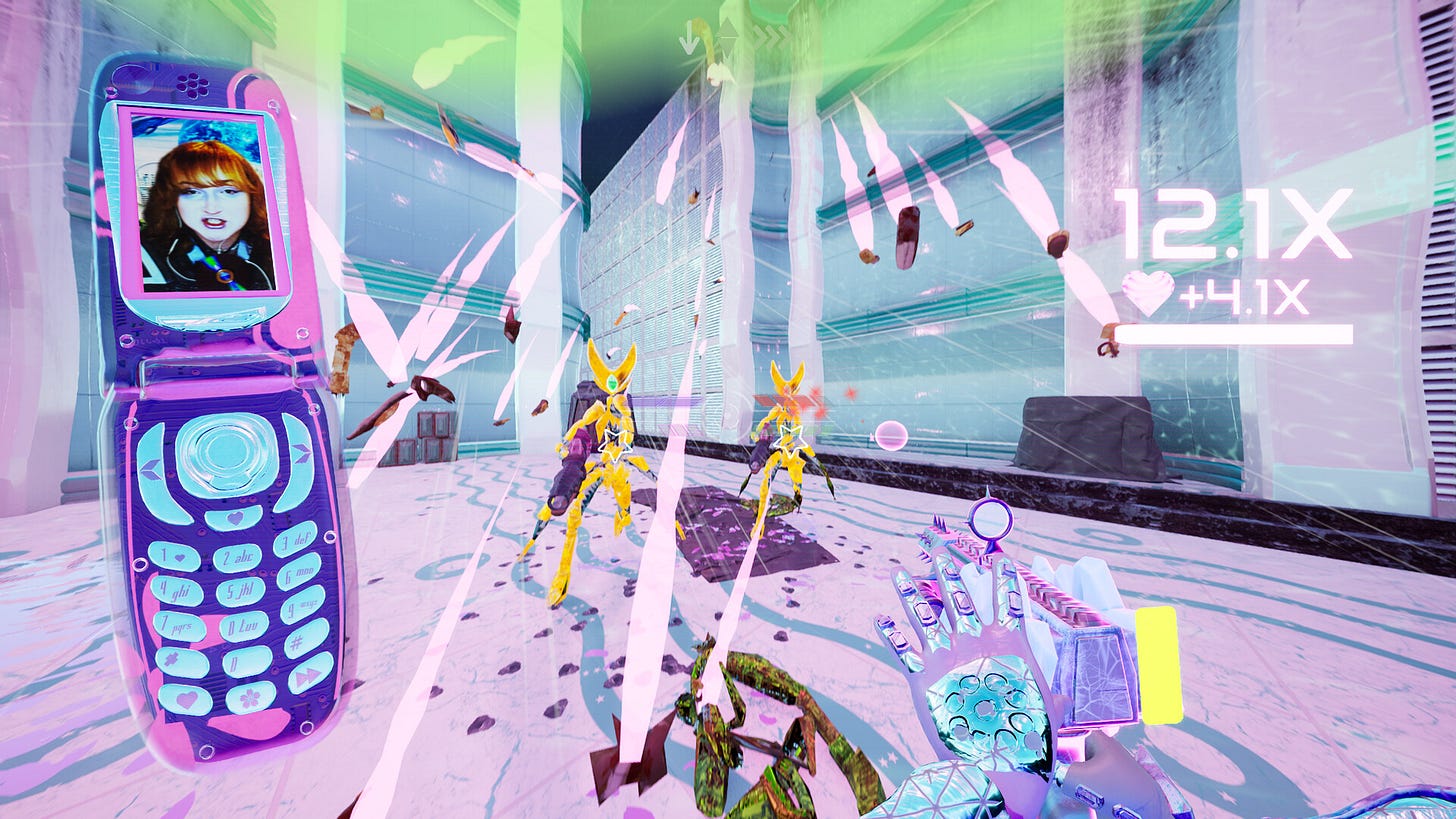

Jane: I've always found 'stylised' to be an interesting word when applied to our game: Incolatus: Don't Stop, Girlypop! When we started the project, it had nothing to do with girlypop aesthetics at all and was more just 'sci-fi arena shooter' as an entire concept. I remember so clearly starting on this project in high school — our very first game for everyone on the team — and going 'I want realistic graphics, well, at least as realistic as Destiny.'

I don't know if I'd say I regret this choice, but it has STRONGLY informed the workflow ever since. There comes a point where you can't redo your art-style, only remix it, and I guess that's where the girlypop factor really starts to come into play.

We were shopping Incolatus around to publishers and trying to get traction online but basically the sentiment was 'we've seen realistic shooter, and you can't do it as good as AAA, so who cares' which I guess in retrospect I understand a lot more. Now I'm not going to be so bold as to say our graphics reached any point of craftsmanship where they deserved to be called 'realistic' but it was obvious what references we were trying to touch on, using all the new and fancy Unreal Engine features with our Substance Painted textures and everything. It was kind of at this point I realised I was way too deep into this 'realistic art-style' to go back and redo all the assets, but what I could do was kind of remix it.

I remember having a light-bulb moment while I was over in Melbourne for games week going down this escalator after a so-so publisher meeting. Our game was never particularly 'stylised' at all but players find their own words for these things, the ones who liked the aesthetic would always talk about the pink guns. All the guns were pink at the time, because they were covered in 'Xyth crystals,' which created an energy that would later be referred to as 'The Love' in game.

I kind of just took this thought and ran with it. Nothing stood out about our game in the genre other than that one colour. So it was like okay, we're not getting any bites anyway, what do we have to lose?

The thought was:'what if the enemies exploded into pink love hearts when you killed them?' Like we keep all the assets as they are, we just, going forward, have in mind that the enemies will now explode into love hearts, and that's something we can add very easily. It sounded very stupid to me but also very fun.

I had no idea how I was going to work this kind of gritty sci-fi game into something where that could make sense but it's like — if we went for it — no one could say we looked like every other game. I guess it just kind of blossomed from there. I got back and prototyped hearts — wow! — then I added little stars.

Eventually, we worked in a gore system for the robots, but instead of exploding into bloody chunks, they would explode into a pink liquid. It was so much fun being in that prototyping stage and going ‘holy shit — this is what our game can actually be, this is so much fun!’

I remember at some point I had this revelatory meeting with our marketing guy, Michal, before our reveal trailer when we were writing our first proper Steam description and it would've been like "Incolatus is a arena-style sci-fi movement shooter" and it just didn't excite me, and I felt at that point it didn't necessarily describe the game either.

It was at that moment when I finally thought aloud 'what if we add the word girlypop to the description?' we just inject that word in there. Because 'sci-fi movement shooter' you go okay, whatever, Titanfall, and maybe with the arena thing it's more like Quake, sure’ but when it's a 'girlypop movement shooter' that's when you're like ‘well I've gotta see that, that's fun, right?’

I guess that's been the other component of it, fun. When the game started it was such realistic and at times dark sci-fi, which honestly made me sometimes depressed and not in good spirits to work on the game. Since the girlypop mindset shift it's just been way more fun to work on! I love seeing people's reactions to our cute little flip phone that talks to you, to our love hearts that come out of enemies, and dress-up mode.

Those were evolutions that only would've happened once I made the choice to say ‘okay this is a girlypop shooter now’, as well as the 'Y2K' descriptor we added to our log-line, which now also guides design. That came out of me at the time being super into Britney Spears and going ‘what defines girlypop?’ Well for me, Britney Spears is up there, and I'm so nostalgic for that era being Gen Z and all.

So I guess to get back to the point somewhat, the line between stylised and not is very blurred. Like for example, here you've got this Unreal Engine semi-realistic graphics sci-fi game, but you spend a year remixing all the assets and recontextualising the gameplay and now you've got a girlypop shooter.

The graphics style was never overhauled, just how it was being used. At some point we injected our sci-fi movement shooter with girlypop and Y2K and those became guiding principles, and so moving forward we still had the same realistic art-style but I guess we drew upon wildly different sources. That created somewhat of a surreal effect for people, especially given the historical context of the genre. Now some people say the art-style is their favorite thing about the game. I guess that makes me happy.

Fergus: I cannot overstate how much that rules, both in the sense that it’s helped the game find a larger audience but also made it more fun to work on. The word remix is I think doing a lot of interesting stuff there though. I can think of lots of AAA games which underwent a similar sort of mid-development pivot, from Borderlands to Bioshock Infinite, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen the word remix deployed around them.

I think when most people see that word, music is the main reference point they have to draw on. However, compared to games, remixed music can often sound a certain way that’s a little easier to identify. Unless you have that extra context of knowing what a game used to be or look like, you’d never know. Returning to that idea of blurred lines, the one between remix and iteration seems pretty porous. Having gone through that process yourself, do you now see other games in a different light? How common is that kind of remixing among Aussie developers?

Jane: I never learned games in any 'proper' or official way so maybe I'm using a word there that isn't very common in the space, that's just how I understand it because I think the concept from music to games is the same. We are taking something that already exists, and changing parts of it to cultivate a different feel whether that be sonically, visually or interactively. For me, I think it's a matter of perspective whether something is remixed or iterated on. Remixing is pretty common in the industry and there's nothing wrong with it.

When I think remix, I think of stuff like Far Cry: Blood Dragon and other expansions/spin offs which largely draw upon an existing asset base and allow players to see them in a new light, but that's of course from a player's perspective, because I never built that game. I like to think we did a similar thing to 'blood-dragoning' Far Cry 3, just during the development of our game instead of after it.

Of course, the benefit we get in that case over Ubisoft is that people hadn't seen our assets in their 'original' context, so to them, our 'remix' isn't a remix. It's just new and I think that's where the distinction lies.

In development, we remixed the set of assets we had created to that point, but to a gamer who will play DSG on release, from their perspective that released product is the start of the journey, so nothing's been 'remixed' yet. If we were then to continue development on that code-base and put out a DLC that remixes assets from an already released game, I think that — to the gamer — is when the game becomes 'remixed.'

For me, Blood Dragon is an easy-to-tell 'remix' because I can clearly see what was carried over from Far Cry 3 having also seen that game. With something like Borderlands, I had no idea until someone told me because I wasn't there for the game's development, so I had no reason to assume anything had changed from the original brief.

You could say that the girlypop shift in Incolatus was a remix to me, as it was such a sudden and severe switch-up. Though, maybe to someone who's coming in fresh, it's just a game that looks like that, and maybe they assume that came around through slow iteration. I guess it's more of an internal-use term than something end-users will identify the game with. I think remixing is something that happens commonly when a game's not working, and I think it's a privilege we have as small indie teams that we can pivot so quickly. I think Aussie developers is the wrong group to look at for that. I think that it's just something that you'll see more commonly in small team sizes.

Fergus: That totally make sense. That said, I don’t know if the two groups are necessarily mutually exclusive. A lot of the data we have about the Australian game development landscape suggests that most developers are operating in smaller team sizes. Perhaps that might go some way to explaining why we see so many Australian-made games bet big on style though.

The advantages of agility aren’t automatic but the fact that so many Australian studios are built around smaller teams does leave them better positioned to remix something that isn’t quite working or standing out into something better built to break into the global gaming conversation. Incolatus is far from the only example of this happening, and it probably won’t be the last either.